More than half the pain is still to come

Fiscal consolidation – cutting the deficit – was the inevitable consequence of the collapse in tax receipts triggered by the 2008 recession. Since 2010 the unprotected budgets in England – those apart from health, education and international development – have been cut by over 30%. Further cuts already planned include reducing central spending on local government between 2013 –14 and 2015 –16 from £16.6bn to £12.1bn.

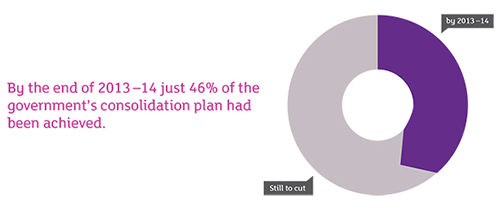

By the end of 2013 –14 just 46% of the Government’s deficit reduction plan had been achieved. Almost three quarters of the total tightening is intended to come from spending cuts. But as the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) points out, we are only a third of the way through the material cuts in public spending, with the easier cuts already made, and tax rises implemented. This means that during the next Parliament people will be seeing economic growth alongside substantial, sustained cuts in services. Historically services have been cut during the bad times; such major reductions at a time of growth are unprecedented.

While public service spending is set to fall by 1.7% a year from 2010 –11 to 2018 –19, the growing population means public service spending per person will fall by an average of 2.4% a year.

Despite the cuts, the government has added to the scale of the task by introducing costly plans such as tax-free childcare and the Dilnot reforms to social care funding. The IFS says ministers have already made additional spending commitments of more than £6 billion a year after 2015 –16, which means there will have to be yet more cuts elsewhere to fund them.

And none of these figures allow for possible future shocks, such as an exit from the EU, energy security problems, cyber risks, further global economic failure or falling levels of tax revenue collected by the exchequer, which have been consistently lower than forecast, prolonging the period of fiscal consolidation further.

An ageing, growing population will increase spending pressures

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) projects that the population will grow by 3.5 million between 2010 and 2018, with the population aged 65 and over growing by 2.0 million.

The IFS estimates that, even if NHS spending continues to be protected in real terms, then between 2010 –11 and 2018 –19, real age-adjusted spending per head on the NHS will fall by 9.1%.

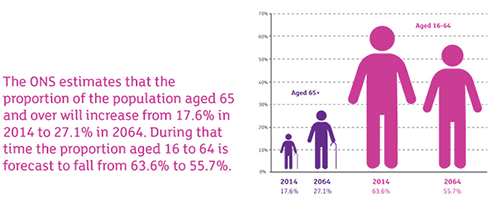

As the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) observes, it is the ageing of the population that has the greatest impact on the future of public finances. The ONS estimates that the proportion of the population aged 65 and over will increase from 17.6% in 2014 to 27.1% in 2064. During that time the proportion aged 16 to 64 is forecast to fall from 63.6% to 55.7%.

Notwithstanding longer working lives, the economically active population will inevitably become proportionally smaller, and at the same time it will need to be even more productive to support the burgeoning generations of older people. Putting aside today’s emotionally charged debates about immigration, there is no getting away from the fact that future governments will need to give much more sober and serious consideration to the types and levels of immigration Britain needs to sustain an economy productive enough to meet the needs of our rapidly ageing population.

Governments will therefore have to spend a greater proportion of national income on supporting older people, meeting costs such as health and social care and pensions. Although improved growth prospects and service reforms should help to an extent, the big choices are limited and clear – if debt levels are to remain sustainable: either taxes will have to go up, substantial cuts will need to be imposed on other budgets such as education, or care and pension levels will need to be cut. There are no other options.

This is a crisis of trust

Addressing these challenges will require strong political leadership. However, trust in politicians and public institutions is declining. According to the 2013 British Social Attitudes survey, the proportion of people that trust governments to put the nation’s needs above those of the political party fell from 38% in 1986 to 18% in 2012.

This increasing deficit of trust calls for a new approach to policy-making. It demands greater honesty, both in the UK and internationally, about questions of long term sustainability, improved transparency of decision making, stronger governance and financial management, and intolerance of costly failures to deliver public services and value for money.